Simplicity of a Database, but the Speed of a Cache: OLAP Caches for DuckDB

2025/12/03 - 18 min read

BYA constant struggle in data is to make everything fast. This holds true for the ingest, for the data pipeline, but most certainly for the visualization part. When you use a BI dashboard and present data to users, you most always have a SQL query in the background that can be slightly complex when you have most logic in your data warehouse and persisted as tables so the query from the BI tool is fast. But sometimes the query does a lot of group bys and aggregation across multiple dimensions on the fly. That's when the response times for these dashboards get very slow, or when we have increased data we analyze, so the query times get longer and longer.

One option is to shift the compute of these SQL queries left, moving them to the dbt or data pipeline, and pre-compute. But sometimes this is not possible, as data needs to be aggregated on the fly as the user wants to switch between dimensions like region, date, product lines, companies, clients, and so on, on the fly. That's why you can't pre-store everything.

Another option that usually comes into play is OLAP cubes, which are optimized for these kinds of queries and serve them really well as they have an internal cache layer and pre-aggregation. But that's another system and another ingestion, combined with engineering work to integrate the pipelines and data on a frequent basis.

Why Would You Add a Cache (with DuckDB)?

What does caching OLAP or databases solve? Why do we invest in it?

The number one reason must be speed and convenience. In times where everyone is vibe coding and not really architecting data applications, at least not in the beginning, the problem of slow result sets and dashboards will appear near instantly.

The usual pain is running a BI query that is super slow. Asking the BI or data engineering team to add an index or a persistent table just for this dashboard might take very long. The usual right decision would be to rearchitect the data flow and have stages for ingestion, transformation, historization and presentation. Basically what we learned with Kimball and classical architecture of data warehouse. But nobody has always enough time for this. So a quick way, even in the traditional architecture, is to add a fast cache just in front of your BI or visualization layer.

The easier this works, the faster it updates and returns results, the better. That's why caching will always be in high demands, as you can compensate for an initial bad architecture and still get quick response times and make the frontend more valuable.

OLAP Cubes Are Dead?

Traditionally, you would add an OLAP cube, or modern OLAP systems to speed up this process if you need sub-second response times. But these are harder to maintain and especially the ingestion part typically needs data engineering as schemas are changing, data will be wrong, and all the plumbing that data engineers do will happen at some point.

But OLAP cubes are essentially a cache too. But what we want is a cache that takes us less effort to build. The perfect examples are DuckDB and MotherDuck, which are quick and easy to use. DuckDB is a couple of MBs binary that can run anywhere, even in the browser. MotherDuck lets you scale and share it across by just changing the path to md: instead of local DuckDB.

Again, we want these three things mostly from a cache:

- Speed: Fast answers in our frontend-facing dashboards, reports and web apps.

- Convenience: Instead of materializing BI queries manually.

- Utilization: It can be easy to run anywhere, to move. A little like a Swiss knife that can do multiple things, simple and easy.

Customer-facing or business-critical data, meaning it must be fast. To build an additional layer with an OLAP system has the downside of being more expensive. An additional OLAP layer needs an additional ingestion step with data pipelines and engineering. On the other hand, an advantage of adding a simple cache is simplicity, no extra work needed (everything happens under the hood).

Different Levels of (OLAP) Cache

If we look at the data landscape, we will find that there are already so many different caches out there, and not only that, we can also cache at different levels of the data flow and lifecycle.

There are different kinds of caches, and on different levels. You can cache inside the BI tools at the application level, you can cache as we talked about before with pre-persisting data mart tables, but you can also use Dremio or Presto that do some caching, and many more.

Different Kinds of Caches (Different Levels)

Let's list the different levels and compare them. Caches can be on different stages along the ETL process.

If we look at the data flow of a data engineering project, we can persist at different levels. The most effective is the closer we are to the visualization, the frontend the user is using. Caching before will only speed up the pipeline and nightly batch job, but not the actual dashboards as they would not profit from that cache earlier in the process.

Potential caching spots, from the customer-facing side, typically right where the visualization happens, to logical and different temperatures of caching:

- Data Apps: application-level caching

- BI Tools: built-in caches

- Notebooks, frontend web apps

- WASM: Open standard for executing binary code in the web and web browser, allowing developers to leverage single binary databases like SQLite or DuckDB. Allowing for more advanced caches directly in the browser while getting the instant speed of DuckDB, created for analytics. E.g. Evidence is using this technology, powering their universal SQL engine built in the browser.

- Hot Cache: Typical application of hot caches in the data warehouse realm is an ODS (Operational Data Store) where the data is prepared for daily and fast consumption when the core data warehouse is too slow as it has too much historical data, and the source database can't be queried. Hot cache is very generic, and any data that is cached, and what we talk about here, could be called hot cache. Another example is message queue that stores data short term (weeks).

- SQL intermediate storage: Probably the most widely used are persistent SQL-based tables. These are tables we either persist as materialized views or executed dbt models. They work best at the data mart level where we prepare and aggregate data in the right granularity for fast and convenient consumption.

- Logical Caches:

- Virtualization and Federation: Not physically stored, but logically joined data tables across different sources, which are then cached in data virtualization tools like Trino, Presto, Dremio.

- Semantic Layer or OLAP Cubes: Typically logical caches as well as we model the data inside a logical model, and then the semantic layer optimizes cache for potential and actual queries. Caching queries and aggregate data efficiently and optimized for consumption.

- Cold Cache: Data Lakes are not really considered a cache, but I'd say we are caching dbt results, old results as backups and even active data to it. Usually we use another technology to warm up this data for fast consumption with MotherDuck, Starlake, and others.

- Zero-copy ETL: DuckDB, Apache Arrow and other approaches that can be used as an intermediate utility to query any data in a fast manner, or zero-copy clone.

I'm sure these layers are not 100% distinct, and there are more categories, but I'd say these are the major ones and they give us a good overview of how to look at caching more broadly, and especially how to apply this for OLAP caches.

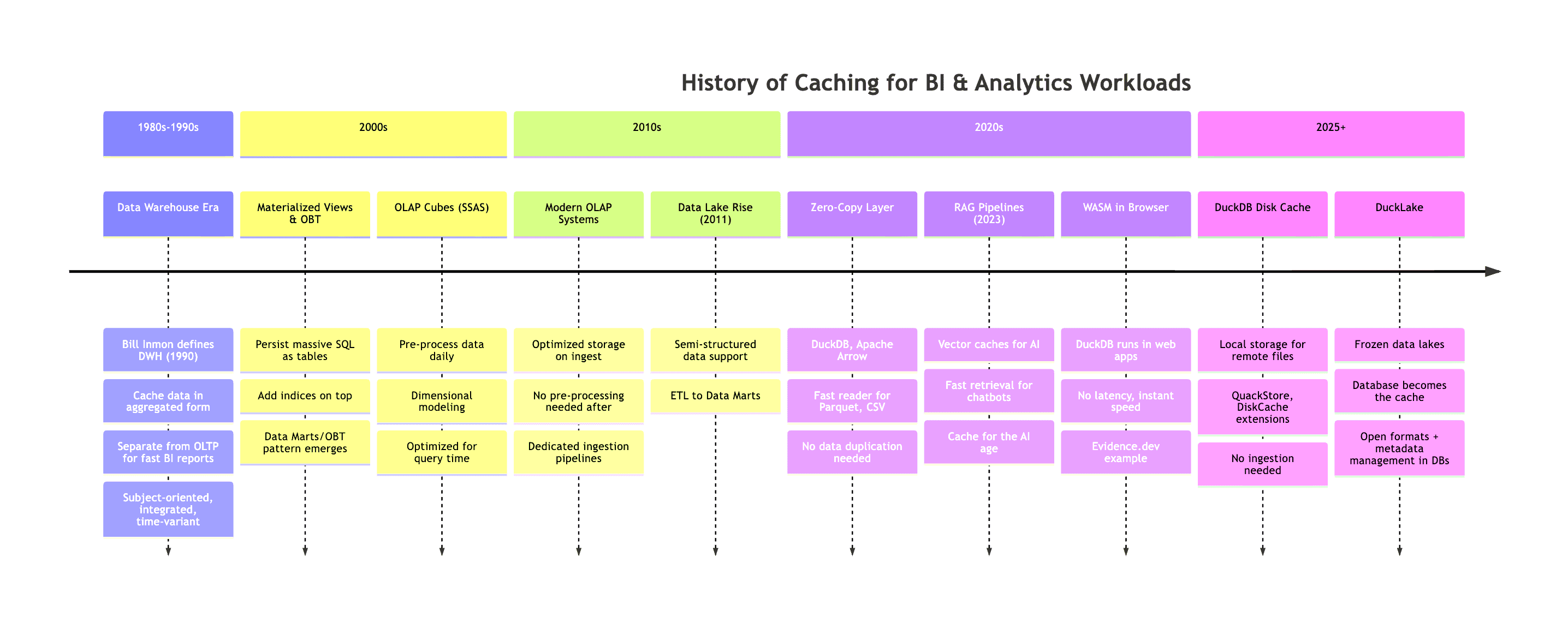

The History of Caching BI Workloads

Besides the different levels, we can also compare two decades back how caching has been implemented differently over time.

As optimizing cache for BI workloads has been one of the most complex problems for a long time, we can take inspiration from it. If caching was solved properly in the past, powering analytics hugely, let's save this work and see how they implemented an additional layer of persisted data with caches over the years.

The chronological history, though not respecting every detail, could go something like this:

It's interesting how the pendulum is swinging forth and back a couple of times from being on the server side to client side to back and in between. From MV, One-Big-Table (OBT) on server-side data warehouses to bringing the data directly to the web application (e.g. WASM), no caching needed as data is super fast available with no latency, or not caching at all with a zero-copy layer with DuckDB and reading super fast with client-powered hardware.

But we can say, to this day, it remains challenging to cache your data independently and in best cases automated. Caching means constantly duplicating data, storing it optimally, and updating data in case the source changes. However, because of the significant outcomes, we still use it in every data engineering solution. Also check out the history of general architecture in data that Hannes Mühleisen was presenting, which gives a lot of insights on how the architecture has not changed much from 1985 to 2015 with adding cloud servers, but shifting more to the clients and small data as we have more powerful clients again.

Key Insights: Positioning, Metadata Management, Freshness Strategies

Key here is also cache positioning. For example, a semantic layer lives between the DWH and the customer, but we might have another web app cache before. So where we should use a cache is always an important question.

Potentially equally important is to query data the fastest way. For this we need a lot of metadata on how our data is stored, what indices we have, what partitions, how wide our tables are, how many rows etc. In a traditional database this is taken care of for us in a declarative way: with SQL!

It's done with indices and even more so with a query planner. Each database has one that interprets the SQL query and tries to find the fastest possible way based on existing metadata it has to query this data without a full table scan, or avoiding other traps that might take an order of magnitude longer to return the data. Metadata management if you will.

Such a query planner also deals with statistics from indices that already tackle probably the biggest challenge of caching, data freshness (vs. staleness). Meaning can I trust the statistics enough to not do a full table scan and return it or is the data outdated and I need to re-read the full table or column.

Strategies and terms we use here are TTL (Time To Live) strategies, cache invalidation patterns, incremental materialization. Or Hot/Warm/Cold data tiering with moving data between tiers based on access patterns and cost optimization.

How about DuckDB and DuckLake?

With DuckDB, we have a whole new set of options. We can already cache in the browser with DuckDB WASM as mentioned above, we can use various extensions that let us on top of the very fast DuckDB queries (CSV, Parquet, etc. reader) either directly stored in DuckDB, or via DuckDB engine stored on S3 or anywhere else.

However, the new features and what we can add on top of it is an additional storage location for cache. Easily configurable and convenient to use, as in querying we do not notice any difference and do not need to manage it other than specifying a location to store the cache.

With DuckLake we even have more options.

The Obstacles to Building a Cache

However, the hard part is to implement a cache. That the cache is always up to date, and not already outdated when we query the cache instead of the real data. That we don't have inconsistencies. See for example the story of Cube and their own-grown Cube Store cache which they built. They initially used Redis for it, but quickly hit the limitations and replaced it with a Rust-written implementation based on Apache Arrow.

But lucky us, with DuckDB, there are open-source implementations we can just use. For example QuackStore or DuckDB Diskcache let you add a cache with maximal convenience. These are especially helpful when we want a cache for a SQL interface. Everything we use SQL for, we might already use DuckDB to query S3 or database tables, or if not DuckDB but SQL, we might use DuckDB as a client and with that get the cache out of the box as explained further down.

What we want is simplicity of a database, but the speed of a cache. Let's look at some examples.

How Does it Work? Examples.

In this section, we look at four caching extensions for DuckDB: QuackStore by Coginiti, cache_httpfs from the community, DiskCache by Peter Boncz (CWI) and an implementation by Striim.

QuackStore

QuackStore speeds up your data queries by caching remote files locally.

The extension uses block-based caching to automatically store frequently accessed file portions in a local cache, dramatically reducing load times for repeated queries on the same data.

How it Works

First install it with:

Copy code

INSTALL quackstore FROM community;

LOAD quackstore;

Set the path you'd like to store the cache on - this is a file system. You can do this with the GLOBAL command:

Copy code

SET GLOBAL quackstore_cache_path = '/tmp/my_duckdb_cache.bin';

SET GLOBAL quackstore_cache_enabled = true;

To test, I turned on the timer and ran a count on a public dataset:

Copy code

.timer on

-- Slow on first try (cold)

select count(*) FROM read_csv('https://noaa-ghcn-pds.s3.amazonaws.com/csv.gz/by_year/2025.csv.gz');

The outcome, first time without cache 49.366, generating it:

Copy code

count_star()

------------

26016543

Run Time (s): real 49.366 user 51.777825 sys 0.449690

second time, cached this time is 3.304:

Copy code

count_star()

------------

26016543

Run Time (s): real 3.304 user 7.630344 sys 0.237343

The cache is 116 MB for this 26 million row dataset. The SUMMARIZE query, that usually takes quite a while as it reads all the metadata and counts of a table, returns much faster:

Copy code

SUMMARIZE FROM read_csv('quackstore://https://noaa-ghcn-pds.s3.amazonaws.com/csv.gz/by_year/2025.csv.gz');

It was faster after, even though this specific question was not cached yet. It only took 4.100 on first run.

You also have the option to cache files that live on a remote server such as data on GitHub or S3:

Copy code

-- Cache a CSV file from GitHub

SELECT * FROM 'quackstore://https://raw.githubusercontent.com/owner/repo/main/data.csv';

-- Cache a single Parquet file from S3

SELECT * FROM parquet_scan('quackstore://s3://example_bucket/data/file.parquet');

-- Cache whole Iceberg catalog from S3

SELECT * FROM iceberg_scan('quackstore://s3://example_bucket/iceberg/catalog');

-- Cache any web resource

SELECT content FROM read_text('quackstore://https://example.com/file.txt');

Based on my research, I need to flag an issue: Peter Boncz's duckdb-diskcache repo doesn't appear to have a working community extension or clear installation instructions. The repo exists but seems more experimental/research-oriented. The cache_httpfs extension (by dentiny) is the actively maintained community extension.

cache_httpfs (DiskCache for Remote Files)

The cache_httpfs extension adds a local disk cache layer on top of DuckDB's httpfs extension. When you query remote files on S3, HTTP, or Hugging Face, it automatically caches data blocks locally and reducing bandwidth costs, improving latency, and adding reliability when connections are flaky.

How it Works

Install and load the extension:

Copy code

INSTALL cache_httpfs FROM community;

LOAD cache_httpfs;

That's it. The extension wraps httpfs transparently, so your existing S3/HTTP queries benefit from caching without any code changes. By default, it uses on-disk caching with sensible defaults.

Example: Querying S3 with Caching

Copy code

-- First query: downloads from S3

select count(*) FROM read_csv('https://noaa-ghcn-pds.s3.amazonaws.com/csv.gz/by_year/2025.csv.gz');

-- Run Time: 42.407s

-- Configure cache location (optional - has sensible defaults)

SET cache_httpfs_cache_directory = '/tmp/duckdb_cache';

-- Second query: caches locally

SELECT count(*) FROM 's3://my-bucket/large-dataset/*.parquet';

-- Run Time: 44.028s

-- Third query: served from local disk cache

SELECT count(*) FROM 's3://my-bucket/large-dataset/*.parquet';

-- Run Time: 1.995s

You can monitor cache behavior with built-in profiling - Check cache hit/miss ratio:

Copy code

SELECT cache_httpfs_get_profile();

┌────────────────────────────┐

│ cache_httpfs_get_profile() │

│ varchar │

├────────────────────────────┤

│ (noop profile collector) │

└────────────────────────────┘

See current cache size on disk:

Copy code

SELECT cache_httpfs_get_ondisk_data_cache_size();

┌───────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ cache_httpfs_get_ondisk_data_cache_size() │

│ int64 │

├───────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ 131048289 │

│ (131.05 million) │

└───────────────────────────────────────────┘

Clear cache if needed:

Copy code

SELECT cache_httpfs_clear_cache();

┌────────────────────────────┐

│ cache_httpfs_clear_cache() │

│ boolean │

├────────────────────────────┤

│ true │

└────────────────────────────┘

The extension supports three cache modes via SET cache_httpfs_type such as on_disk (default) persists cache locally, survives restarts. in_mem for fast but lost when DuckDB closes and noop for disable caching entirely.

What Gets Cached

Beyond raw data blocks, the extension also caches file metadata to avoids repeated HEAD requests, glob results for speeds up patterns like s3://bucket/*.parquet and file handles for reduces connection overhead. This is particularly powerful for Data Lake patterns (Iceberg, Delta, DuckLake) where Parquet files are immutable and the cache can be trusted indefinitely.

DiskCache

DiskCache is a DuckDB extension that adds disk (SSD) caching to DuckDB's built-in RAM cache.

DuckDB already caches remote Parquet data in RAM via its ExternalFileCache. DiskCache adds a local disk layer underneath, so when RAM fills up, data spills to SSD rather than requiring another network fetch.

NOTE: No easy way to install yet No easy way to install yetDiskCache currently requires building from source. It may become a community extension in the future. keep an eye on the repository for updates.

How it Works

By default, DiskCache only caches files accessed through Data Lakes (Iceberg, Delta, DuckLake) where Parquet files are immutable. For other remote files, you can enable caching via URL regex patterns:

Copy code

-- Configure cache with regex to match NYC taxi data

FROM diskcache_config('/tmp/diskcache', 8192, 24, '.*d37ci6vzurychx.cloudfront.net.*');

-- First query: downloads ~450MB of parquet files

SELECT count(*) FROM read_parquet([

'https://d37ci6vzurychx.cloudfront.net/trip-data/fhvhv_tripdata_2024-01.parquet',

'https://d37ci6vzurychx.cloudfront.net/trip-data/yellow_tripdata_2024-01.parquet',

'https://d37ci6vzurychx.cloudfront.net/trip-data/green_tripdata_2024-01.parquet'

]);

-- Second query: served from disk cache

SELECT count(*) FROM read_parquet([...]);

-- Inspect cache contents

FROM diskcache_stats();

In-Process Columnar Caching with DuckDB with Striim

Striim wrote a great example of how to go Beyond Materialized Views using DuckDB for in-process columnar caching. They decided to not use Materialized Views (MVs) in Postgres for their use case because they have a lot of dynamic queries and therefore work with imperative languages for cache maintenance logic. The second reason was the infrastructure overhead with MVs and the limited flexibility that Postgres materialized views brought to the table by speeding up complex queries but requiring manual refreshes and lacking incremental updates for frequent changes.

Another benefit they had with DuckDB was to control the cache maintenance logic in Python.

DuckDB runs embedded in their control plane, refreshing static data (users, tenants) daily and dynamic metrics every minute. PostgreSQL stays the source of truth for writes while DuckDB handles all analytical reads.

On modest hardware (4 vCPUs, 7GB RAM) they showcase a 5–10x speedup with zero additional infrastructure costs:

| Metric | Before | After |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | 3.95 tasks/sec | 11.71 tasks/sec |

| Execution time | ~4 sec | ~0.8 sec |

| Latency | — | 0.19–0.2 sec |

John Kutay notes in above article that it isn't true HTAP since there's no real-time consistency between systems, but for operational analytics where slight staleness is acceptable, it's a pragmatic middle ground: pluggable OLAP performance without the complexity.

Can We Skip Redis? Immutable DataLake?

Typically Redis is used as a key-value store cache for data that require quick access. So could we replace Redis with DuckDB?

As long as the data is frozen (immutable), we could use something like DiskCache above. We'd need benchmarks to compare actual speed, but focusing on functionality alone, it's a pragmatic and simple solution.

You could extend this further with an immutable DuckLake, called Frozen DuckLake: a read-only, serverless data lake with no moving parts. It's just a DuckDB file on cloud storage with near-zero cost overhead. No servers, no refresh jobs, no cache invalidation because the data never changes.

This pattern works especially well for caching historical reference data (e.g., past fiscal years, archived reports), lookup tables that rarely update, or snapshots for auditing or compliance.

The cache becomes the database. Or rather, the database becomes the cache.

Other Examples

There are many more examples that we could talk about. You could use Apache Arrow for an in-memory cache, but you'd need to implement an application logic for that yourself, or use pg_duckdb to run a |HTAP Database directly on top of the OLTP source database, meaning we could avoid ETL and duplication of data.

You can also use an out-of-the-box solution that manages the cache for you in the cloud like MotherDuck. Working well with the examples shown here with DuckDB, easy to switch from local to cloud. Something that just works.

Wrapping Up

Caching remains one of the most practical tools in a data engineer's toolkit, especially in imperfect data architectures where you need quick results for common queries. What we've explored in this article is how DuckDB and its ecosystem offer a refreshingly simple path to speed with minimal configuration, no separate ingestion pipelines, no new systems to maintain.

QuackStore and DiskCache implement read-through caching transparently, while Frozen DuckLake elegantly sidesteps the notoriously difficult cache invalidation problem by embracing immutability. No TTL strategies to tune, no stale data to worry about. Sometimes the best cache pattern is no pattern at all, just well-defined principles or a simple extension that can be installed easily through community extensions in DuckDB. This can drop query times from minutes to just a few seconds in the best case scenario, making your dashboards usable again.

The broader insight is that caching swings like a pendulum and has come full circle. From the early days of data warehouses and OLAP cubes, through materialized views and semantic layers, we've arrived at something surprisingly simple: the database as the cache. With DuckDB's fast readers, WASM support for browser-based analytics, and patterns like Frozen DuckLake for immutable reference data, we have ways of skipping the complexity of traditional cache infrastructure if needed. Metadata management, query planning, and freshness strategies come baked in, as we use an actual database for our cache delivered in a lightweight and portable binary format.

If you want something that just works without wrestling with cache invalidation or spinning up additional infrastructure, MotherDuck gives you server-side caching that's fast out of the box. Just swap your local path to md: and you're running in the cloud with all the speed benefits intact. Give it a try and see how simple high-performance analytics can actually be. Read more in the Docs for more information.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Start using MotherDuck now!

PREVIOUS POSTS

2025/11/19 - Diptanu Gon Choudhury

Unstructured Document Analysis with Tensorlake and MotherDuck

Learn how to query unstructured documents with friendly SQL!

2025/11/24 - Simon Späti

Branch, Test, Deploy: A Git-Inspired Approach for Data

This article explores how to bring Git style workflows like branching, testing, and deploying to your data stack. Learn how concepts like zero copy cloning and metadata pointers can finally give you isolated test environments.