My personal reflections from watching Jordan Tigani’s keynote "The Unbearable Bigness of Small Data" at Small Data SF last month.

There's something surreal about sitting in the audience watching your co-founder give a talk that touches on the very conversations that led to starting a company together. As Jordan took the stage at our second Small Data SF conference, I found myself transported back to those early discussions—the ones where we questioned everything the data industry had been telling us for years.

What followed was less a product keynote and more of a manifesto. Jordan laid out a vision for how we should think about data scale, why the industry got so much wrong, and what it means to design systems for how people actually work rather than for theoretical edge cases.

The Story That Started It All

Jordan opened with a story I'd heard before, but it hits differently when you hear it in front of a room full of practitioners who've lived through the same frustrations. About five years ago, when he was at SingleStore, Jordan pitched the idea of open sourcing a single-node version of the database. The CTO's response wasn't that it was technically unsound or that it wouldn't work with real workloads.

The response was simply: "People are going to laugh at us."

That's it. Not "this won't work." Not "customers won't want it." Just... people will laugh.

And here's the thing—Jordan had actually seen some of SingleStore's biggest customers, including Sony, running on massive scale-up machines rather than distributed clusters. It was working great. The objection wasn't technical. It was social. It was about how the database community would perceive them.

Sitting in the audience, I watched Jordan turn this rejection into a philosophy. If someone's going to laugh at you for building something, maybe that's actually a signal worth paying attention to. As he put it, "If there's an area where somebody might laugh at you for building something or thinking something, then maybe it's not a bad idea."

Owning the Joke

This led to what I think is one of the most important cultural decisions we've made at MotherDuck—and it's something that confuses people who don't understand what we're doing. We dress up in silly costumes. We lean into the absurdity. We make jokes about small data.

"If somebody's gonna laugh at you, the best way to deal with that is to own it and to be like, no, no, no, this is my joke. And I'm going to let you in on the joke. Then we can all laugh together."

- Jordan Tigani

It's not just a marketing ploy (though it does help people remember us). It's an invitation. The whole point of the Small Data conference is to create a space where people can admit something that feels almost shameful in our industry: their data isn't that big. And that's completely fine.

Jordan shared another story that crystallized why this matters. When we were first thinking about starting the company, someone told him about going to big data conferences and getting all fired up about Netflix's architecture and all these massive distributed systems. Then they'd go home and think, "What am I going to do, run a one-node Spark cluster?"

That person felt like they weren't a real data engineer because they weren't operating at Netflix scale.

I looked around the room as Jordan said this. I could see people nodding. That feeling—that somehow your work is less legitimate because you're not processing petabytes—is something a lot of practitioners carry around.

Jordan's response to this stuck with me:

"The scale at which you're operating has nothing to do with how important it is what you're doing, how hard it is what you're doing, how impactful it is what you're doing."

Then came the moment I knew was coming, but it still made me smile. Jordan got the entire room to repeat after him:

"I've got small data."

It sounds silly. It is silly. That's the point.

The Two Axes of Scale

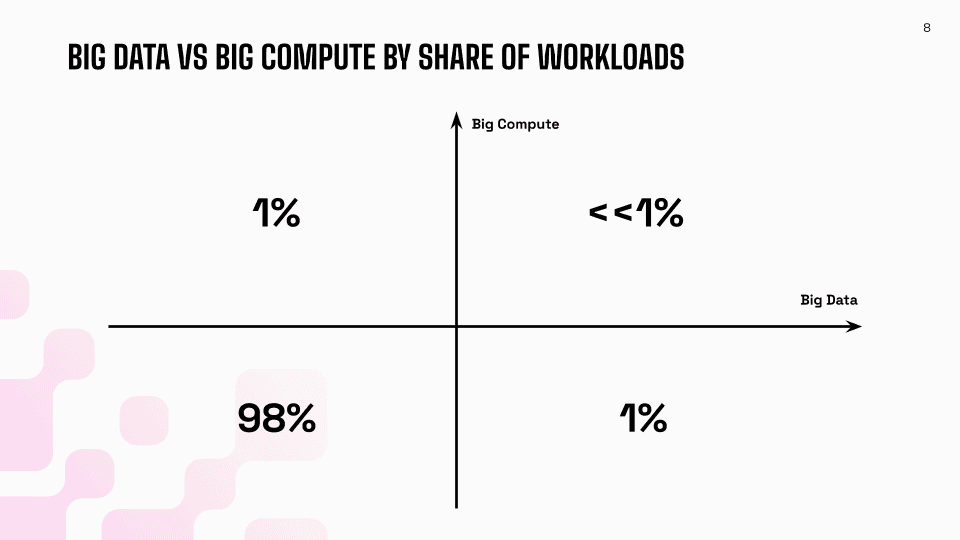

After the group therapy session, Jordan moved into the more technical meat of the talk, and this is where things got really interesting. He presented a framework for thinking about data scale that I think should fundamentally change how people evaluate their infrastructure needs.

Once upon a time, there were boxes. You bought a database server, and if you ran out of capacity, you bought a bigger box. Bigger boxes were exponentially more expensive. Then cloud came along, and we separated storage from compute. This separation created something important that Jordan highlighted: what we used to call "big data" is actually two different things.

First, there's literally the size of your data—gigabytes, terabytes, petabytes sitting somewhere. But with object storage like S3, this dimension has become almost boring. You put your data on S3, it's virtually infinite, and you kind of stop thinking about it.

Second, there's big compute—the actual processing power you need to work with that data. And here's the key insight: machines are enormous now. What doesn't fit on a single machine today is radically different from what didn't fit on a single machine fifteen years ago.

Jordan drew a two-by-two matrix on the screen: big data versus small data on one axis, big compute versus small compute on the other. And then he dropped a stat that made people laugh: "Somebody actually was saying to me yesterday that in Supabase, the median database size is 100 rows. Not even 100 megabytes, gigabytes, whatever. It's 100 rows."

The vast majority of workloads—and I mean the vast majority—live in the small data, small compute quadrant.

What Actually Lives in Each Quadrant

Jordan walked through each quadrant systematically, and this breakdown was genuinely useful for understanding where different workloads fall.

Small data, small compute: This is where most SQL analysts live. Ad hoc analytics, your gold-tier data, data science exploration. Most of what people actually do every day falls here.

Small data, big compute: This is interesting. Your BI layer often ends up here, not because the data is big, but because you have lots of users hitting the same datasets. A bunch of people refreshing dashboards, drilling into different dimensions—that takes compute, even if the underlying data is modest. Analytics agents also fall into this quadrant.

Big data, small compute: Jordan called this "independent data SaaS"—situations where you're building a SaaS application where each customer has separate data. In total, storage might be significant, but any individual query doesn't need much compute. Time series and log analytics also fit here—you're adding data continuously but typically only querying recent windows.

Big data, big compute: This is the corner case. You're rebuilding tables, running model training over entire datasets. These workloads do exist, but they're not what you're doing most of the time.

The Backhoe Problem

Jordan then made an observation that I think cuts to the heart of what's wrong with so much data infrastructure. When software engineers design systems, a fundamental principle is that your design point—the thing driving your architecture—should be the main use case, not the corner cases.

He told a joke about needing to remove some roots from his yard, requiring a backhoe.

"And so of course I get a backhoe and drive that to work every day."

It's absurd when you put it that way. But that's exactly what the data industry has been doing. Because you occasionally need to rebuild a table, you're using a giant distributed system every day when it's totally unnecessary.

The older modern data stack systems were designed for the top right corner of that quadrant—maximum scale, maximum compute. And their attitude toward the bottom left corner (where 98% of actual work happens) was essentially, "I'm sure it'll work if you scale down. I'm not going to worry about it."

Jordan shared a story from his time at BigQuery. They made a change that added a second to every query. The tech lead's response was: "It's fine." Because they cared about throughput for giant workloads, not latency for interactive queries.

But here's the thing:

For the vast majority of what people are doing, latency is what matters. Not throughput. You're not trying to churn through petabytes. You're trying to get an answer quickly so you can ask the next question.

Designing for the Common Case

What if we designed from the bottom left instead of the top right? What if we made sure that quadrant worked beautifully first, and then figured out the scaling problems when they actually arise?

Jordan laid out what he believes such a system would look like:

Scale up, not scale out: You can scale up really, really far these days. Scale out is complicated, adds latency, and introduces all sorts of coordination problems. Why pay that cost if you don't need to?

Store data at rest on object storage: This gives you effectively infinite scalability on the storage dimension. Data is immutable, highly durable.

Ephemeral, cloneable compute: Because the data is durable in object storage, your compute can be ephemeral. You can spin it up, shut it down, clone it. This enables what Jordan called "hypertendency"—giving each user their own database instance rather than jamming everyone into a shared system.

He mentioned Glauber's work at Turso, running hundreds of thousands of SQLite instances where each user gets their own database. The scaling model isn't "one giant database." It's "lots of small databases."

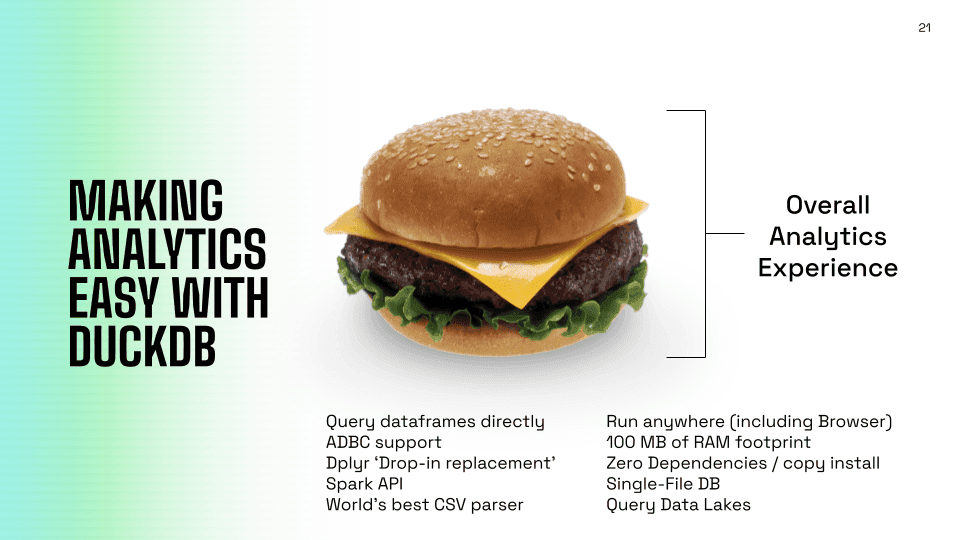

DuckDB and the Whole Burger

Jordan pivoted to talking about DuckDB, and even though most people in the room were probably familiar with it, the framing was useful. DuckDB is an in-process analytical data management system that's been, as Jordan put it, "taking the world by storm." The GitHub stars have an exponential curve. The downloads are enormous. He joked that it's probably one of the top five websites in the Netherlands by traffic.

But why? Why is DuckDB so successful?

Jordan's answer: they make things easy. The whole experience, not just the core database functionality.

He used a burger metaphor. Database companies tend to focus on the patty—the query engine, the storage format, the core performance. Everything else—how you get data in, how you integrate with tools, the overall user experience—gets treated as somebody else's problem.

DuckDB focuses on the whole burger. They have what Jordan called "the world's best CSV parser." That might sound trivial, but anyone who's wrestled with a malformed CSV—null characters embedded in random places, types that change partway through the file—knows how much time that can consume. If you spend more time wrestling data into your system than you do actually querying it, your fancy query engine doesn't matter that much.

md:

Jordan showed two code snippets. The first was plain DuckDB in Python—import the library, open a connection, run queries. The second was MotherDuck. The only difference? Adding "md:" as a prefix to the database name.

That's it. Same code. Same interface. But now it's running in the cloud, with all the infrastructure we've built around it.

I've seen this demo many times, obviously, but watching the room's reaction was gratifying. The simplicity is the point. You shouldn't need to completely restructure your code or learn a new paradigm just because you want cloud-scale durability and collaboration.

Ducklings and Isolation

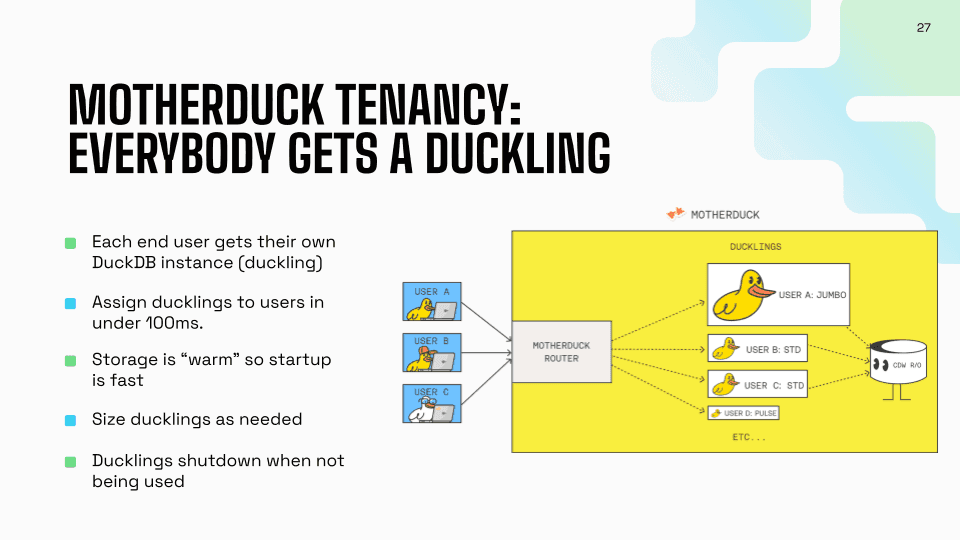

Jordan explained our tenancy model, which I think is genuinely differentiated from how traditional data warehouses work. In traditional systems, you have lots of users hitting the same shared infrastructure. You provision for peak load, and one user can stomp on another user's performance. Auto-scaling is always behind the curve.

In MotherDuck, everybody gets a duckling—our term for individual DuckDB instances. We can spin up a new duckling in under 100 milliseconds, faster than human reaction time. Each user is isolated. They can scale up independently, and they shut down immediately when not in use.

This model works particularly well for the small data, big compute quadrant. Think about BI tools—Jordan mentioned Omni, who was at the conference. When you have lots of users hitting BI dashboards, you need lots of compute, but each user might be looking at the same underlying data. With read scaling, we can run multiple DuckDB instances against the same data, each serving different users.

Why Agents Get Me Excited

Jordan spent time on analytics agents, and this was probably the section where his enthusiasm was most palpable. I think he sees this as one of the most interesting application areas for the infrastructure we've built.

The problem with text-to-SQL approaches is the one-shot assumption. You ask a question, the system generates a query, and you either get your answer or you don't. But that's not how human analysts actually work.

Jordan posed a question: "Which of my customers are at risk of churning?"

A human analyst doesn't one-shot that. They don't type out a single perfect query and get "customers A, B, and C." They investigate. They look at multiple data sources. They form hypotheses, test them, refine them. They say, "Oh, maybe I need to pull in this other dataset." It's iterative.

Agents can work this way. They can explore, hit dead ends, try different approaches. But this means you need infrastructure that can handle lots of parallel, independent exploration. If every agent query is hitting the same shared resource, you're going to have problems. One agent's heavy query will impact another's.

With our tenancy model, each agent can get its own duckling. They can scale independently. They can even branch data, modify it speculatively, and return to previous states. The isolation model that works well for human users also works well for agent users.

DuckLake and the Metadata Problem

Jordan introduced DuckLake, an alternative to Iceberg for open table formats. Iceberg stores its metadata on S3 as a web of JSON and Avro files. It works, but there's overhead. Every time you need to understand what's in your table, you're making multiple object storage calls, parsing files, navigating a complex structure.

DuckLake takes a different approach: store the metadata in a database. The database knows how to do transactions, filtering, and fast lookups. It's what databases are designed for.

The data itself still sits on object storage, so you get all the durability and scalability benefits. But operations that need to understand table structure or metadata can be dramatically faster.

Jordan mentioned that the DuckLake creators—Hannes and Mark from DuckDB Labs—have done benchmarking on petabyte-scale DuckLakes, and it just works. Because as long as your query operates over a reasonable subset of the data, the metadata lookups are fast and the data access is efficient.

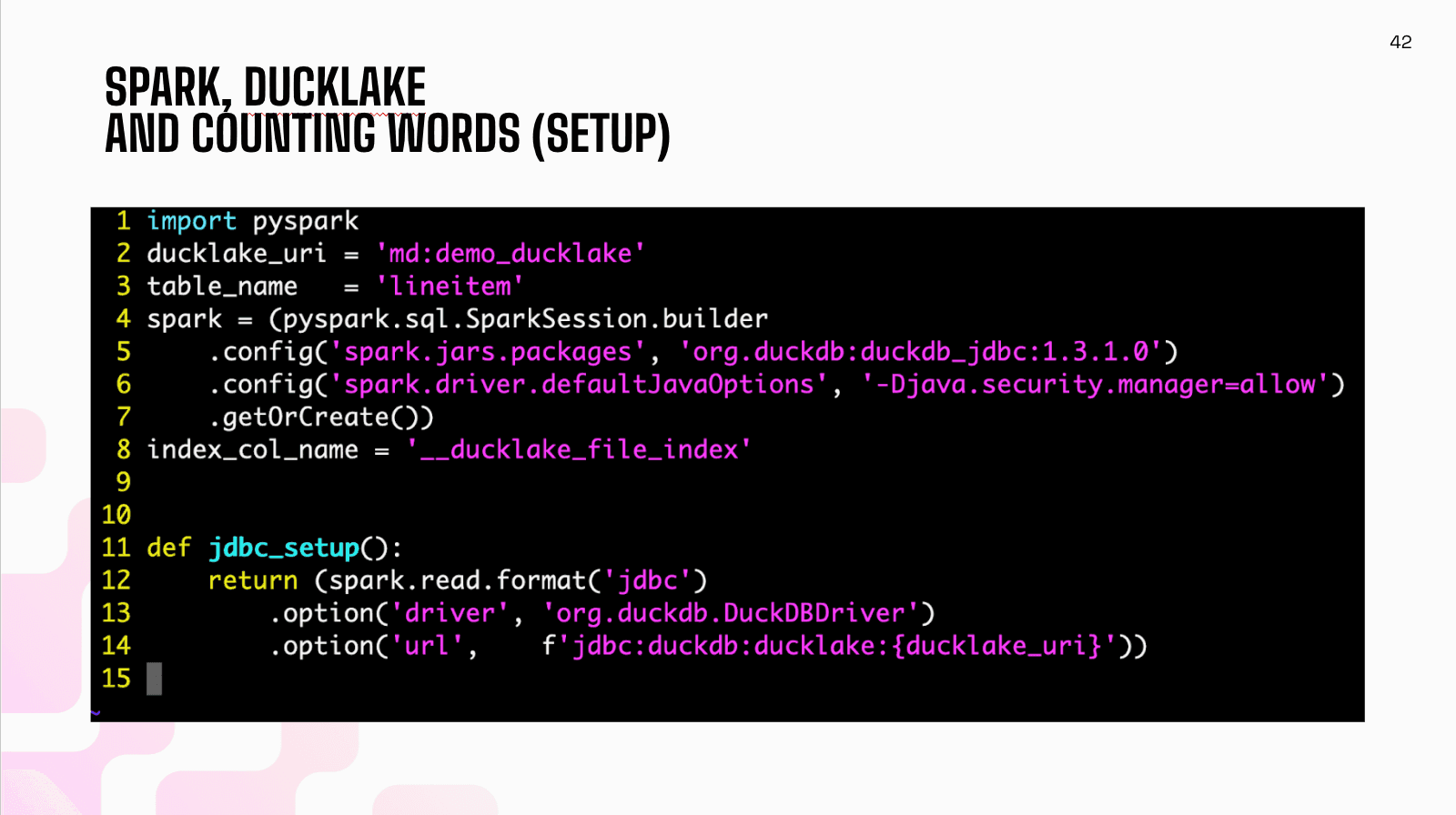

One thing he showed that impressed the room: a working Spark connector for DuckLake in 34 lines of Python. Most of that is boilerplate. Try writing a production-quality Iceberg connector in 34 lines.

When You Actually Need Big

Jordan didn't pretend that big data, big compute workloads don't exist. They do. Sometimes you need to rebuild entire tables. Sometimes you need to run training over your full dataset.

For those cases, we've recently released what we call mega and giga instances—the largest is 192 cores and a terabyte and a half of memory. Jordan noted that's more memory than a Snowflake 3XL, which costs around a million dollars a year. The vast majority of workloads can be handled on single instances.

But beyond that, because DuckLake is an open storage format, you can just run Spark on it. It's an escape valve. You're not locked in. If you truly have workloads that require massive distributed processing, the data is right there in object storage, in a format that Spark can read.

Jordan ended with a reference to the Dremel paper from 2008—the original technology behind BigQuery. When that paper came out, it was seen as science fiction. The queries they demonstrated seemed impossibly fast at impossibly large scales.

Today, you can run those same queries on a single machine with similar or better performance, especially if you've pre-cached some data. What seemed like it required a massive distributed system fifteen years ago is now within reach of a laptop.

The Full Picture

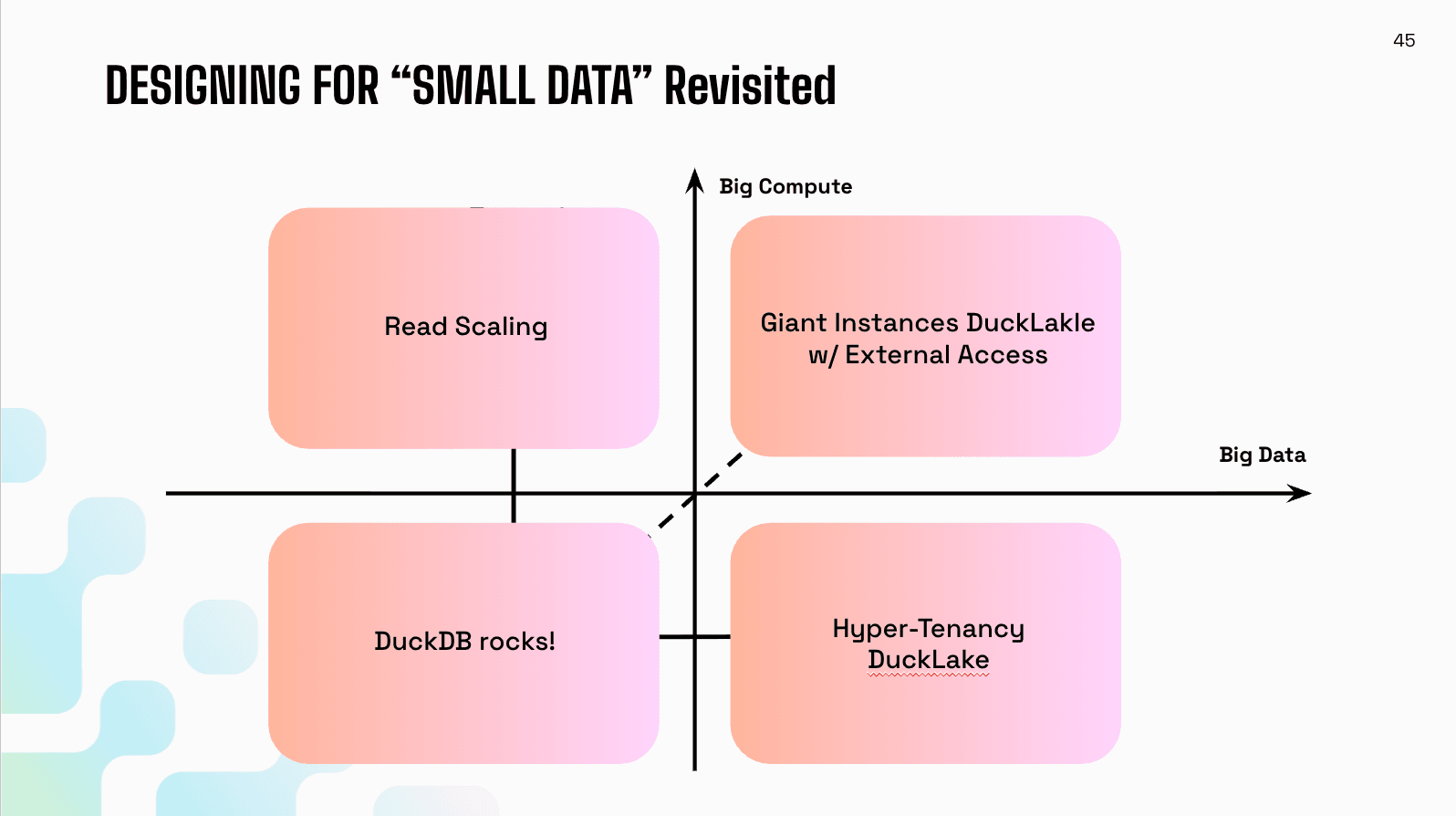

Jordan wrapped up by mapping our solutions back to the quadrant. Small data, small compute—DuckDB rocks here. Increase the data size—DuckLake and hypertendency have you covered. Increase the compute—read scaling handles it. And for the actual big data, big compute corner—giant instances and DuckLake's openness to external engines.

As Jordan left the stage, I felt something I hadn't expected: pride, mixed with a sense that we're still early in making this vision real. The ideas Jordan presented aren't just theoretical—they're reflected in actual shipping software that thousands of organizations are using. But there's so much more to build.

The small data movement isn't about being anti-big-data. It's about being honest about what most people actually need and designing systems that serve those needs brilliantly, rather than forcing everyone to pay the complexity tax for scale they'll never require.

I've got small data. And apparently, so do most of you.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Start using MotherDuck now!

PREVIOUS POSTS

2025/12/17 - Jordan Tigani

Building an answering machine

Discover how MotherDuck's MCP server enables true self-service analytics through AI agents. Query data in plain English with Claude, ChatGPT, or Gemini—no SQL required.

2025/12/18 - Till Döhmen

Building the MotherDuck Remote MCP Server: A Journey Through Context Engineering and OAuth Proxies

How MotherDuck built a production-ready remote MCP server—from OAuth proxy challenges with Auth0 to tool design patterns that help AI agents query data warehouses effectively. Includes lessons from a hackathon where agents ran 4,000+