The Unbearable Bigness of Small Data

2025/11/05Featuring:TRANSCRIPT

Small Data Conference Keynote: Designing for the Bottom Left

Thanks so much for coming out to our second Small Data Conference. I'm super excited to have so many people here, so many familiar faces, so many people from around the data community, so many practitioners. I think we had a nice workshop day yesterday where people actually felt like they got some real stuff done.

A Personal Story About "Small Data"

To start out with, I'd like to go into a little bit of a personal story. About five years ago when I was working at SingleStore, we were thinking about open-sourcing a single node version of SingleStore. When I pitched this to some internal folks, the CTO said to me, "If we have a single node version, a small data version of the database, people are gonna laugh at us."

I thought that seems sort of silly, because he didn't say it was a bad idea. He didn't say this isn't going to work or this isn't going to work with real workloads, because we had actually seen some of our biggest customers—Sony was running on these sort of giant scale-up machines and it was working great. But it was just sort of like, "Oh yeah, the database people are going to laugh at you."

As an aspiring entrepreneur, if there's an area where somebody might laugh at you for building something or thinking something, maybe it's not a bad idea. There's a lot of examples of people who have built amazing things that people laughed at. If somebody's going to laugh at you, the best way to deal with that is to own it and be like, "No, no, no, no. This is my joke and I'm going to let you in on the joke. Then we can all laugh together."

You may wonder why sometimes we dress up as silly things at MotherDuck. It's not just a marketing ploy, although it is nice—first they ignore you, and as a startup people are going to ignore you unless you come up with a way to get them not to. But it's also so that we can invite people in to laugh together at, "Hey, isn't this all ridiculous?"

The Real Data Engineer

A couple years later, I was thinking about starting a company with some other folks like Ryan who's here. I was talking to some people about what we were thinking about building, and one of them said, "I go to these big data conferences and I get all fired up and I'm like, yeah, the Netflix architecture is so cool. I go home and it's like, well, what am I gonna do—run a one-node Spark cluster?"

He felt like he wasn't a real data engineer because he wasn't operating at this huge scale. I thought that was sort of unfortunate and unfair because the scale at which you're operating has nothing to do with how important what you're doing is, how hard what you're doing is, or how impactful what you're doing is.

Sheila kind of touched on it earlier—we wanted this to be sort of a tongue-in-cheek conference because we're in on the joke. It's small data, and we believe that the size of the data you're operating on, the scale you're operating at, has nothing to do with how important it is. And we're going to have some fun.

The Small Data Mantra

I want everybody to repeat after me. The small data mantra is: I've got small data.

Ready? I've got small data.

One more. One more time. Everybody together. I've got small data.

Awesome. Thank you so much. That was my big job for the day—I got everybody to say I've got small data.

Rethinking Data Scale

I also want to talk a little bit about what we're seeing in the shapes of data. How data scales is maybe a little bit more rich than we tend to talk about it.

Once upon a time there were boxes. You bought a box. This box was your database. If you ran out of space on that box, you had to buy a bigger box, and the bigger box was probably a lot more expensive.

Then came cloud. We separated storage and compute. We got to break up those boxes. But then we actually realized that there's two different axes here. There's compute—in general a larger amount of compute was sort of linear scaling, not exponential scaling, which is a big difference. And then storage—you just put your storage on object store and it's kind of boring. You put it on S3. S3 is virtually infinite, virtually infinite bandwidth. You kind of don't have to worry about it as much anymore.

When you have separation of storage and compute, big data is now two different things. What you used to call big data because you had this big box with a bunch of storage and compute—there's two separate axes. First, there is literally the size of data that you have. If it's data that can't fit on a single machine, won't fit in your laptop, won't fit in your workstation—that's a real thing. But typically you just put it on object store and you don't think about it again.

Big Compute vs. Big Data

Big compute actually is probably the more interesting one, which is I think one of the reasons why we've built these scale-out distributed systems—super complicated. But also, machines are huge now. What doesn't fit on a single machine is very, very different than what didn't fit on a single machine 15 years ago.

I published a blog post a while ago called "Big Data is Dead." Sheila referenced it earlier. It's not really that big data is dead, because saying that it's dead doesn't make it go away. But it's actually kind of big compute that isn't as important.

The Quadrants of Data

If we look at the landscape, we have big data on one axis and big compute on the other axis. The vast, vast majority of workloads are in the small data, small compute quadrant. In fact, somebody was saying to me yesterday that in Supabase, the median database size is 100 rows. Not even 100 megabytes or gigabytes—it's 100 rows. There's just a lot of small data out there.

If you look at cost, obviously the small data, small compute doesn't tend to cost you very much. If you go to big data, big compute—well, compute tends to be a little bit more expensive than storage, so that can be pretty expensive. Big data, small compute—if you have a lot of data, maybe you're generating some logs over time, they just sort of sit there, and you're doing small amounts of compute over the recent data. That's a little bit more expensive than when you didn't have a lot of data. And then when it gets really expensive is when you have big data and big compute.

If you look at the workloads that fall in each of these boxes, you see a lot of what a SQL analyst does tends to be in the small data, small compute side of things—gold tier work. Your BI actually may push into the big compute because very often you have a lot of users, a bunch of people all hitting on the same dataset, refreshing their dashboards, drilling into different things. That does take more compute.

Then when you get into the big data side, I call it "independent data SaaS"—where you're building a SaaS application where each one of your users has separate data. If each one of your users has separate data, you might not actually need a whole lot of compute, but in total, the amount of storage might be a lot. And then there is, every once in a while, sometimes you need to rebuild your data sets and run model training over the whole dataset. Yes, those workloads do exist.

Design for the Primary Use Case

I was a software engineer for 20 years, and one of the primary rules of thumb for when I was building something was you wanted to make sure that the design point—the primary thing that you're building, the thing that drives your architecture—is the main use case and not the corner cases.

As a bad example, I needed to remove some roots from my yard and needed a backhoe, so of course I get a backhoe and drive that to work every day. That's a little bit of an absurd example, but that's kind of like, "Hey, I have every once in a while I need to rebuild my tables, so I'm going to use this giant distributed system every day when it's totally unnecessary."

The Old Way: Designed for Big Data, Big Compute

If you think about how a lot of the older school modern data stack systems are designed, they were designed for the top right corner—"Hey, we can handle the biggest scale, the biggest compute, the biggest data." And then like, "Yeah, I'm sure it'll work if you scale down the amount of compute," because of course it's going to work. "And of course it's going to work if you scale down the data size. And the bottom left corner stuff? I know that's 98% of what you're doing, but I'm not even going to worry about that or care about that."

Just as an example, in BigQuery at one point we ended up making a change and it added a second to every query. The tech lead at the time was like, "It's fine," because in general the thing that we cared about was the top right corner, and the stuff that people were doing that was trying to be interactive didn't matter.

If you think about the performance goals, the top right corner—you want throughput because you have a lot of data to churn through and you're willing to add a second because you're not concerned about latency. But the vast majority of things you're doing, latency is the important part.

The New Way: Design for the Bottom Left

What if instead we designed for the bottom left corner? We made sure that it was going to work and we had solutions for when we scaled up the data sizes. We made sure it was going to work when we scaled up the compute sizes and figure it out when you get to the top corner. I mean, it is a requirement—you can't ignore it. It is a requirement that that stuff is going to work, but you can use a little bit of elbow grease to make that work.

Building from Scratch

So if you were building a system from scratch, what would you do? Well, I believe you'd want to use scale up, not scale out, because you can scale up really, really far and scale out is a lot of work.

You store data at rest on object store, so then you kind of get the infinite scalability, and that means you have to sort of change some of the semantics—the data is immutable and you have to do a bunch of fun things. But if data is stored on object store, it means that it's highly durable, and so your compute can be ephemeral. You can clone, you can stamp out lots of those.

Hypertenancy

Who's familiar with hypertenancy? Heard that as a word? Glauber is, because that's what he started calling what they're doing in Turso with running lots and lots of SQLite instances. Each user gets their own SQLite instance, and you scale by not having a giant one but by just having hundreds of thousands or millions of users, and each one gets a different database.

Introducing DuckDB

You may have known this was coming. I wanted to talk a little bit about how we are handling some of these things, and to do that I want to give a little bit of background.

These days probably most people have heard of DuckDB. It's an in-process analytical data management system. It's been taking the world by storm. This is the code you need to do in Python to install DuckDB and start running queries—it's super easy. The GitHub stars have this nice exponential shape. The downloads have this very nice shape. I think it's actually probably in the top five websites in the Netherlands by the amount of traffic that it gets. It's been growing by a lot.

The reason that people like it is because they just make it easy. Having worked on other databases and other database companies, in a database company you tend to focus on the patty of the burger if what you're serving is a burger. You focus on the patty—how you get data in, how you get data out, how you integrate with other things. The general experience is something that is sort of like, "Oh, that's somebody else will deal with that, that's partners, that's something else." DuckDB does a really good job of just making the whole experience great.

To give an example, I think they have the world's best CSV parser. If you have this nasty CSV that has some goofy null characters in the middle of it and has some things that may change type from one part of the file to the other, wrestling with that and getting that in can take a lot longer than you end up waiting for your queries to run. So solving those problems is actually important.

MotherDuck: DuckDB in the Cloud

At MotherDuck we're taking DuckDB and we're running it in the cloud. This is the code you need to run to run DuckDB in the cloud. It's exactly the same code that I had before except I just changed the name of the database to have the prefix md: and that means it runs in the cloud. That's all you have to do.

Small Data, Small Compute

So big data versus big compute—how does this work for MotherDuck?

If you look at the quadrant, the bottom left quadrant—small data, small compute—I mean, everybody knows DuckDB works great here. The things you want to do here are ad hoc analytics, you're doing your platinum and gold tier stuff, you're writing a bunch of SQL queries, you're doing data science. You can scale this up as needed. That's pretty straightforward. That's right in the sweet spot of the design.

This is a visualization of a database benchmark from ClickHouse. Inexpensive goes up, faster goes to the right. If you look at inexpensive but slow, you've got the distributed small databases. If you look at the expensive but pretty fast, we've got the distributed large databases. And then kind of up on the top right, both inexpensive and fast, is DuckDB. This is actually from several months ago—if you look at the most recent results, they're actually further up and to the right.

Small Data, Big Compute

One of the problems with traditional data warehouses and the tenancy model that they have is basically you have lots of users hitting the same thing. I think it's a legacy from the days where you had the box—everybody shares this one box. You need to provision for the peak versus the instantaneous amount. One user can often stomp on other users or impact other users' access. Autoscaling tends to be behind, so from a price-performance perspective, it's not ideal.

In MotherDuck, everybody gets a duckling. We call our DuckDB instances ducklings. MotherDuck—we marshal and care for the ducklings in the cloud. A new user shows up, we can assign them a duckling in less than 100 milliseconds, so less than human reaction time. We keep things on warm storage so we can run queries super fast. Every user gets their own duckling, so they're all isolated. They can scale up to essentially the largest size that we need, and then they shut down immediately after they're not being used.

This can be helpful on small data, big compute, because small data, big compute is when I may not have a lot of data but I might have a lot of users using that data. As mentioned before, kind of a BI tool—Omni, the Omni folks are here. Omni supports MotherDuck using read scaling, which means that we can run lots of DuckDB instances against the same BI data.

Analytics Agents

Agents is also a really interesting one. Joe talked a lot about agents. If you have an analytics agent that's going to be operating over data, you can have lots of analytics agents that are all operating over the same data. That's a lot of compute, a lot of work that they're doing, but it may not be a lot of data.

The way that read scaling works in MotherDuck—every user gets their own duckling, but also each end user of the BI tool gets their own duckling, and we will route that to a separate replica. It should be stable, so the same user tends to be querying the same data. You can decide how many you want so that you don't have essentially infinite costs.

On the subject of agents, I'm actually really excited about agents because I feel like—and this may be kind of a preview of the talk that I have with some other folks in the BI space and observability and transformation a little bit later—text-to-SQL has some limitations if you're trying to ask questions of your data. I think agents is a really good way of solving some of these problems because agents means that you don't have to one-shot it. You don't have to come up with a perfect query that solves your problem.

Here's an interesting question that if you asked a human analyst: "Which of my customers are at risk of churning?" A human analyst is not going to one-shot that query. They're not going to type out this query and boom, "Oh, it's these three." They're going to investigate. They're going to look at a bunch of things. They're going to pull in data from different sources. They're going to think about it and be like, "Oh, maybe I need this." That's the kind of thing that an agent can do.

What would you need from your underlying system? You need to be able to spin up lots of different instances because each one of those agents is going to be a different system. As Joe mentioned, there's a good chance those are going to melt down your single server. But if each one can scale individually, then you have a lot better chance of being able to handle that load. You can clone data. They can all be operating—they may even be modifying data as they go, and you maybe want to sort of branch and return to a previous point. The tenancy model that we have tends to work pretty nicely for that.

Big Data, Small Compute

Onto the third quadrant—big data, small compute. I think the biggest thing here is time series workloads or logs analytics workloads. There's just a lot of big datasets. Actually at Google we used to say all big data is created over time. Giant datasets don't all of a sudden just sort of show up.

Typically what people end up doing is they're adding a small bit at a time or they're looking at a small bit at a time. They're looking at what happened in the last day, the last week. They're looking at your Datadog, looking at your observability data—what's going on right now. This is where hypertenancy comes into play, and then Duck Lake.

Typically the way SaaS provisioning works, if you're using a monolithic database, is you have lots of customers, you funnel those into a web application, and then you talk to a database. That's pretty standard. But you have to provision for peak, you have to be able to handle the scale, and then users aren't isolated.

With MotherDuck, we can actually have each end user talk directly to the database without even going through a backend. You don't even have to route things through the backend, and then they can be provisioned on demand and scale up and down, be isolated, etc.

Duck Lake

I mentioned Duck Lake. Iceberg is sort of all the rage these days. Duck Lake is an alternative to Iceberg that instead of storing the metadata in S3, stores data metadata in a database. It makes things a lot cleaner. You don't have these sort of goofy multitude of web of JSON and Avro files that point to all this metadata on disk. You have a database that knows how to do transactions, knows how to do filtering and pushdowns very, very fast.

I think Duck Lake is also a key to being able to do larger scale because it's a data lake—or a lakehouse. The data sits on S3. You can add as much as you want. The metadata is in a database, and as long as the query that you're doing is only operating over a reasonable amount of that data, then it should just work.

Duck Lake was created by the creators of DuckDB—Hannes and Mark and DuckDB Labs—and they've done some benchmarking on petabyte-scale Duck Lakes, and it just works.

Big Data, Big Compute

The last quadrant is big data, big compute. Every once in a while you do have to do some of these giant transformations. You have to rebuild tables. You want to run model training over your whole dataset.

You can still use this in MotherDuck. First of all, we have these giant instances. We just released these—we call them mega and giga. The largest of which is 192 cores, a terabyte and a half of memory. That's more memory than is in a Snowflake 3XL. A Snowflake 3XL is a million dollars a year. So if you have workloads that you need more than a 3XL for that single workload, you might need something bigger. But the vast, vast, vast majority of things can be handled.

But then if they can't, one of the nice things about Duck Lake is we can actually give physical access to the data and you can just run Spark. You have this sort of outlet valve because it's an open storage system.

The Evolution of Performance

When it came out, the Dremel paper came out in 2008. It was seen as like, wow, this is science fiction. Some of the queries that they ran, we basically could do now on a single machine and get similar performance or better performance, especially if you had pre-cached some of the data. If you had to read it from S3, there are potential bottlenecks from reading from S3. But in general, just because you're storing it on object store—object stores are really not great as a database.

In order to create a Duck Lake in the MotherDuck UI (also the same as the DuckDB CLI), it's just a couple lines of code: CREATE DATABASE TYPE DUCKLAKE. That's really all you need to do. Then you adopt your Parquet files and then you're up and running.

Also, just wanted to show one of the cool things about Duck Lake—this is a working Spark connector in Python that is 34 lines of code, but most of that is sort of boilerplate setting things up. It's super easy to do. If you just contrast that with how much code you'd need to build a working Iceberg connector and have it be properly distributed, I guarantee it would be a lot, a lot more than that.

Summary: Design Points

Just getting back to the sort of the design points that we're looking at: small data, small compute—DuckDB rocks. If you increase the data size, we have Duck Lake and we have hypertenancy. If you increase the compute side, we have read scaling. And then for the actual big data, big compute, we have giant instances, and then Duck Lake which also can have external access.

Thank you.

Transcript

0:00[music]

0:05[music]

0:11Thanks so much for coming out to our second small data conference. Uh I'm super excited to have uh have so many so many people here, so many familiar faces, uh so many people kind of from around the the data the data community, so many practitioners. I think we had a nice um workshop day yesterday where people, you know, actually felt like

0:31they got some real real stuff done. Um to start out with, I'd like to kind of go into a little bit of a personal story. um about five years ago when uh I

0:43was I was working at single store and we were thinking about open-sourcing a single node version of of single store and when I pitched this to some you know some internal folks the CTO said to me he said if if we have a single node version a small data version of the database um people are gonna laugh at us

1:03and and I thought like that seems that seems sort of silly because he didn't say it was a bad idea He didn't say like no no no like this isn't going to work or this isn't going to work with real workloads because we had actually seen some of our biggest customers you know run Sony was running on these sort of giant scale up machines

1:21and like they were having you know it was it was working it was working great but it was just sort of like oh yeah the database people are going to laugh at you and you know as an aspiring entrepreneur you know if there's an area where somebody is going to you know might laugh at you for for building

1:35something or thinking something then you know maybe it's not a bad maybe it's not a bad idea. There's a lot of examples of people who have buil built amazing things that you know people laughed at.

1:45You know, if somebody's going to laugh at you, the best way to deal with that is is to own it and to be like, "No, no, no, no. Like, this is my joke and I'm going to let you in on I'm going to let you in on the joke. Then we can all laugh together." And so, you know, you

1:58may wonder why, you know, sometimes, you know, we dress up as, you know, silly silly things. uh at at Motherduck it's not just a it's not just a marketing marketing ploy although you know it is it is nice you know you know first they ignore you like yeah as a startup people are going to ignore you unless you

2:14unless you kind of uh come up with a way to get them not to but then also it's so that we can invite people in to to sort of to laugh together at sort of you know hey isn't this all isn't this all ridiculous so a couple years later um I was thinking about, you know, starting uh

2:33starting a company, you know, with with some other folks like Ryan who's here and um and I, you know, I was talking to

2:42some people about what we were thinking about building and um you know, one of

2:48them said uh you know, I was like, I go to these like these big data conferences and I get all fired up and I'm like, yeah, the Netflix, you know, architecture is so cool. And he's like, I go home and it's like, well, what am I gonna do like run a one node Spark cluster? And it's like and he felt like

3:03he wasn't a real data engineer because like he wasn't operating at this at this huge scale. And like you know I thought that was sort of that was unfortunate and unfair because like the scale at which you're operating has nothing to do with how important it is what you're doing like how hard it is what you're doing how impactful it is what you're

3:24doing. And so, you know, Sheila kind of touched on it a little bit um, you know, earlier when she said, you know, we kind of wanted this to be sort of a tongue-in-cheek kind of conference because it's like it's like, hey, you know, you know, we're in on the joke is like, hey, you know, it's small data and

3:41we we believe that like the size of the data that you're operating, the scale that you're operating, um, has nothing to do with how important it is. And we're going to have some fun. I want everybody to repeat after me. The small data mantra is like I've got small data.

3:56Ready? I've got small data. Are we do what? One more. One more time. Everybody together. I've got small data. Awesome.

4:05Thank you. Thank you so much. All right. That that was my uh you know big uh you know job for the day. I got everybody to say I've got small data. But I also want to talk a little bit about what we're seeing in uh in in the shapes of data.

4:19And I think how data scale is is maybe a little bit more more rich than we tend to talk about it. So once upon a time there were boxes. You know, you bought a box. This box was your database. This box was your um you know, whatever system you were using. And if you ran out of space on that box, you had to buy

4:37a bigger box. And the bigger box was probably a lot more expensive. Uh then came cloud. And then we separated storage and compute. And we separated to storage compute. We got to break up those boxes.

4:48Um but then we actually realized that there's two different axes here. There's there's compute um and you can you know in general a larger larger amount of compute was sort of linear scaling not uh exponential scaling which is a big difference. And then storage you just put your storage on object store and it's and it's kind of boring. It's like

5:07you know you put it on S3. S3 is virtually infinite. It's virtually infinite bandwidth. Um you kind of don't have to worry about it as much anymore.

5:15Of course the semantics change all that stuff but like um but really when you have add separation of storage and compute um you kind of have you know big big data is now two different things.

5:27What you used to call big data because you had this big box this big box that had a bunch of storage and compute like there's two separate axes. There's first there is literally the size of data that you have and if it's you know data that can't fit on a single machine it won't fit in your laptop won't fit in your

5:42workstation like that's a real thing. Um but typically you just put it on object store and you don't you don't think about it again. Big compute actually is probably the more interesting one which is I think one of the reasons why you know we've built these scale out distributed systems you know super complicated. Um but also machines are

6:02huge now like what doesn't fit on a single machine is very very different than it than what didn't fit on a single machine 15 years ago. You know I published a blog post a while ago called big data is dead. Sheila referenced it earlier. Um it's not really that big data is dead because you know big data

6:19saying saying that it's dead doesn't make it go away. Um but it's actually kind of big compute that we that um that isn't as important. If we look at the kind of the the the landscape of you know we have big data on one axis and then big compute on the other axis. The vast vast majority of workloads are in

6:39the small data small small compute. In fact, somebody actually was saying saying to me yesterday that in Superbase the median database size is a 100 rows.

6:50Not even a 100 like megabytes, gigabytes, whatever. It's 100 rows. Um, and so there's just a lot of small data out there. If you look at cost, okay, so obviously the small data is small compute. It's like it doesn't tends to not cost you very much. Um, if you go to big data, big compute, well, compute tends to be a little bit more expensive

7:07than than storage. So that can be pretty expensive. Big data, small compute, you know, if you have a lot of data, you know, maybe you're generating some logs over time, they just sort of sit there.

7:18Um, and you're doing a small amounts of compute over the recent data. Like, okay, that's a little bit more it's more expensive than when you didn't have a lot of data. Uh, and then when when it gets really expensive when you is when you have big data and big data and big compute. If you then look at the like

7:33the workloads that um that kind of fall in each of these each of these boxes, you see a lot of kind of what a SQL analyst does tends to be in the small small data small compute side of things.

7:44Uh you know, gold tier. Um your BI actually may push into the to the big compute because you're going to have very often you have a lot of users. You have a bunch of people all hitting on the same data set, you know, refreshing their dashboards, drilling into different things. Um that does take more compute. Um, I'll talk a little bit more

8:01about analytics agents. Uh, then when you get into the big data side, um, I call it independent data SAS. And what I mean by that is where, uh, you're building a SAS application where each one of your users has separate data. Uh, and if each one of your users has separate data, you might not actually need a whole lot of compute, but uh, you

8:21know, in in total, the uh, the amount of storage might be a lot. And then there is, you know, for big compute, there is, you know, every once in a while sometimes you need need to rebuild your data. you rebuild your data sets and you need to run you know model training over the whole over the whole data set and

8:34you know yes those uh those workloads do exist. So I was a software engineer for 20 years and uh and one of the kind of the primary rules of thumb for when I was like building something was you wanted to make sure that the design point the primary thing that you're building you know you're build the thing

8:52that drives your architecture is the main use case and not the corner cases as a bad example you know I had to get you know remove some roots from my yard and so needed a backhoe and so of course I you know get a backhoe and you know drive that to work every day Uh, I mean that's, you know, a little bit of an of

9:10absurd example, but that's kind of like, you know, hey, I have every once in a while I need like this I need to rebuild my tables, so I'm going to use this sort of giant distributed system every day when it's when it's totally unnecessary.

9:24So kind of if you think about how a lot of sort of the older school modern data

9:30stack uh systems are designed is they were designed for the top right corner the hey we can handle the biggest scale the biggest compute the biggest data um and then like yeah I'm sure it'll work if you know you scale down the amount of compute like because of course it's going to work uh and of course it's

9:47going to work with uh if you scale down the uh the data size and you know for the you know the bottom left corner stuff like I I know that's 98% of what you're doing, but like I'm not even going to worry about that or or care about that. And just sort of as an example, um you know, in BigQuery at one

10:03point we ended up uh we ended up making a change and it added a second to every query and like and the you know the tech lead at the time was like it's fine like because in general the thing that we cared about was the top right corner and like the stuff that people were doing that was that was trying to be

10:19interactive didn't didn't matter. But if you think about what the kind of the the goals like the performance goals are, you know, the the the top right corner, you want you want throughput because you have a lot of you have a lot of data to churn through and like you need like you're willing to add a second because

10:37because you're not concerned about latency, but the vast majority of things you're doing like latency is the important uh is the important part. What if instead we designed for the bottom left corner? We made sure that like it

10:52was going to work and we had solutions for when we scaled up the data sizes. We made sure it was going to work when we scaled up the the compute sizes and you know figure it out when you when you get to the top corner. I mean we like it is a requirement. You can't you can't ignore it. It is a requirement that that

11:07stuff is going to work but like you kind of can use a little bit of elbow grease to make that to make that work. So if you were building a system from scratch what would you do? Well, I believe, you know, you'd want to use scale up, not scale out. Um, because, you know, you can scale up really really far and scale

11:26out is kind of uh it's a lot of work. Um, you know, you store data at rest on object store. So, then you kind of get the infinite infinite scalability and that means you have to sort of change some of the semantics and the data is immutable and you kind of have to do a bunch of bunch of fun things. Um but if

11:42if data is stored on object store means that it's um it's you know highly durable and so your compute uh can be ephemeral and you know you can clone you can stamp out lots of those um hypertendencies who's who's familiar with hypertendencies heard that as a word glber Glober is uh because you know that's what he started calling what

12:06they're doing in torso with um you know running lots and lots of my SQL instances is uh and we have >> sorry SQLite I'm sorry [laughter] apologies yes SQLite um uh lots of SQLite instances and you know each user gets their own SQLite instances instance and and uh and you scale by not having a giant one but you scale by just you can

12:30have hundreds of thousands of users or millions of users and each one gets a different database.

12:35Um so uh you may have known this was

12:40coming you know the I wanted to talk a little bit about about like how we are handling some of these things and and to do that I want to kind of give a little bit of background um you know these days probably most people have heard of heard of duct DB um but it's an inprocess uh analytical datab data management system

12:56uh it's been taking the world by storm you know this is like the the the code you need to do in Python to install DB and start running start running queries so it's it's super crazy. Um, you know, the the GitHub stars have sort of have this nice nice exponential shape. Uh, the downloads uh have this, you know,

13:16very very nice shape. I think it's actually probably at the number top five website in um in the Netherlands by the amount of traffic that it that it gets.

13:27So, it's been uh it's been growing by a lot. And the reason that people like it is because they just make it easy. So having worked on other database other databases and other database companies like in a database company you tend to focus on the patty of the burger if that's what if what you're serving is a

13:44burger you focus on the patty like the how you get data in how you get data how you get data out how you uh how you integrate with other things like the general experience is something that that is sort of like oh that's somebody else will deal with that that's partners that's that's something else and ductb does a really good job uh of just making

14:03the whole experience great. And to give an example, I think they have the best the world's best CSV parser. Uh, and so like just a lot of time like if you have like you get this like nasty CSV that has some goofy like null characters in the middle of it and like it has some things that may like change type from

14:20one, you know, one one part of the file to the other like wrestling with that and getting that in can take a lot longer than you end up waiting for your queries to run. So like solving those problems is actually is actually important.

14:35So at mother duck we're taking ductb and we're running it in the cloud. Um and this is you know uh the code you need to run uh to run motherduck uh to run in to run ductb in the cloud. It's exactly the same code that I had before except I just changed the name of the database uh to have the

14:55prefix mdon and that means it runs in the cloud and that's all you have to do.

15:00So big data versus big compute. So how does this how does this work for for mother duck? So if you look at the quadrant the bottom left quadrant the you know small data small compute I mean like everybody knows I think duct DB works works great works great here and like kind of the things you want to do

15:16here are you know ad hoc analytics um you're doing your platinum and gold tier stuff uh you're writing writing a bunch of SQL queries you're doing data science um and you know you can scale this up as as needed that's that's pretty that's pretty straightforward that's right in the sweet spot of the design design Um this is kind of a visualization of uh a

15:38database benchmark um uh that from click house and um you know the inexpensive

15:46goes up faster goes to the right and you know if you kind of look at the inexpensive but slow you've got the distributed small databases. If you look at the expensive but uh pretty fast, we've got the um the distributed large databases. And then kind of up on the top right, the both inexpensive and fast is is duct DB. And this is actually this

16:10is from a couple several months ago, like if you kind of look at the re most recent results, they're actually further up into the up and to the right. Um

16:19so one of the things with uh you know the problems with you know kind of traditional data warehouses and and the tendency model that they have is basically you have lots of users kind of hitting the same thing and that's what like I think it's a legacy from the days where you had you had the box you had

16:35like hey this is you know everybody shares this one box and um you know you need to provision for for for the peak versus kind of the uh versus the instantaneous amount um one user can often stamp on you know other users or impact other users other users access um and uh you know autoscaling tends to be

16:56tends to be behind so you know from a price performance it's not it's not ideal in motherduck everybody gets a duckling we call we call our duck DB instances ducklings you know mother duck we marshall and you know care for the ducklings in the cloud um and uh and so a new user shows up we can assign them a

17:13duckling in 100 less than 100 milliseconds so less le than human reaction time and we keep things on warm storage so you know we can run queries super fast and then every user gets their own duckling and so they're all isolated uh they they you know they can scale up to you know essentially the largest size that we that we needed and

17:30then they shut down immediately after they're not being used so this can be helpful on this small data big compute because small data big compute is when you know I may not have a lot of data but I might have a lot of users using that data and so you know as mentioned before kind of a BI tool Um, Omni, the

17:46Omni folks are here. You know, Omni uh supports uh, you know, mother duck using, you know, read scaling, which means that we can run lots of duct DB instances uh against the against the sort of the same the same BI BI data.

18:01Um, agents is also a really interesting one. Um, you know, Joe talked a lot about agents and you know, if you have an analytics agent that's going to be operating over data, you can have lots of analytics agents that are all operating over the same data. That's a lot of compute. That's a lot of work that they're doing, but it may not be a

18:18lot of data. So, kind of the way that read scaling works in in motherduck every, you know, I mentioned every every user gets their own duckling, but also each end user of the BI tool gets their own duckling and that we will route that to a separate replica. um and that each rep and it should be stable. So the same

18:35user tends to have you know maybe querying the same the same data and you can decide how many you want so that you don't have essentially infinite um infinite costs.

18:46On the subject of agents, um I think I'm actually really excited about agents because I feel like um and this may be kind of a preview of the talk that I'm that I have with um uh with some other

19:00other folks uh in the BI space and uh and observability and transformation uh a little bit later. But, you know, text to SQL is is has some limitations if you're trying to do uh I you know, if you've got if you want to ask questions of your data and um and I think agents is a really good way of solving some of

19:20these problems because agents means that you don't have to oneshot it. You don't have to come up with a perfect query that says that solves your that solves your problem. Like here's a here's an interesting question that if you asked a human you a human analyst like which of my which of my customers uh are at risk of churning like a human

19:38analyst is not going to oneshot that query they're not going to like type out this query and like boom oh it's these these three they they're going to investigate they're going to look at a bunch of things they're going to pull in data from different sources they're going to think about it and they're like oh maybe I need this and like and that's

19:51the kind of thing that an agent can do and so what would you need from your underlying system from your underlying system, you need to be able to spin up lots of different instances because each one of those agents is going to be a different system. Like as Joe mentioned, like there's a good chance that those are going to melt down, you know,

20:05whatever your, you know, your single server is. But if each one can scale individually, then you have a lot better chance of being able to handle that load. Um, and you can, you know, clone data. They can all be oper, you know, they they may even be modifying data as they go and you maybe want to sort of

20:21branch and um uh and return to uh to a pre a previous point. So the tendency model uh that we have tends to work pretty nicely for that.

20:30So onto the third quadrant the big data small compute and I think that the the key you know the biggest thing here I think is like there's like time series workloads or logs analytics workloads there's just a lot of you know a lot of big data sets um actually at Google we used to say all all big data is created

20:47over time and um you know like giant

20:51data sets don't all of a sudden like just sort of show up and and so um

20:57typically what people end up doing is they, you know, they're adding adding a small bit at a time or they're looking at a small bit at a time. They're looking at, you know, what happened in the last day, the last week, you know, are looking at, you know, looking at your data dog, uh, looking at your, uh,

21:11your observability data, like what's going on, what's going on right now. So, this is where hypertendency comes into into play. Uh, and then duck lake. Um, and uh, I'll talk a little bit about ducklake in just a minute, but um, so typically the way SAS provisioning works for if you're using a monolithic database um, is you have lots of

21:32customers, you funnel those into a web application and then you talk to a database like that's pretty that's pretty standard. Um, but you know you have to provision for peak you know have to be able to handle the scale etc. and then users aren't isolated. And so this is again you know the the uh with with motherduck we can actually have each end

21:50user talk directly to the database without even going through a backend. So you don't even have to sort of route things through the backend and then they can be provisioned on demand and scale up and down be isolated etc.

22:01Um I mentioned ducklake uh you know iceberg is sort of is all the rage these days. Um, Ducklake is an alternative to to iceberg that instead of storing the metadata in S3 stores data metadata in a database. Uh, and it makes things, you know, a lot cleaner. Um, you don't have these sort of goofy multitude of, you

22:25know, web of JSON and AVO files that point to all these this metadata on on on disk. you have a database that knows how to do transactions, knows how to um you know do filtering and and push downs very very fast. Um and um talk a little

22:43bit about that more in uh you know later but uh you know I think ducklake is also a key to being able to do um to being

22:53able to do larger scale because it's a data lake. It's like it's or a lakehouse. The you know the data sits on sits on S3. you can add as much as you want. um you know the the metadata is in a is in a database like and as long as the query that you're doing only is operating over a reasonable amount of

23:11that data then it should it should just work like and so you know um the the data lake was create ducklake was created by the creators of ductb um hanis and mark um and and ductb labs and they've kind of done some benchmarking on you know pabyte scale duck lakes and you know it just it it works

23:31um so the Last quadrant is, you know, big data, big compute. You know, every once in a while you do have to do some of these giant transformations. You have to rebuild tables. You have, you know, you want to run model training over your whole over your whole data set. And um you can still use this in in motherduck.

23:46So, first of all, we have these giant instances. We just released these um you know, we call them mega and giga. The largest of which it's 192 cores, a terabyte and a half of memory. Um that's more memory than it is in a Snowflake 3XL. A Snowflake 3XL is a million dollars a year. So if like if you have

24:03workloads that um that you need more than a 3XL for that single workload, you might need something might need something bigger. But um you know the vast vast vast majority of things can be can be handled. Um but then if they can handle one of the nice things about ducklake is um ducklake can you know we

24:23can actually give physical access to the data and you can just run spark. So you can run you know it's like okay we have this you have this sort of outlet valve um because it's because it's an open um open storage system. So um when it came out you know Dremel was like the Dremel paper came out in 2008. Um it was seen

24:42as like wow this is this is like science fiction and some of the queries that they ran um we basically could do um we

24:51could do now on a single machine and and get and get similar performance or better performance uh especially if you had pre-cached some of the uh the data if you had to read it from S3. you know there is you know I I I'm uh potential potential bottlenecks from um from reading from from S3 but in general just

25:10because you know just because you're you're storing it on on on object store object stores are really not great as a are not great as a as a database um you know in order to create a ducklake in uh in in uh this is in in the mother duck UI is also the same as the ductt UI um

25:27it's you know just a couple lines of code create database type ducklake and um and that's really all you need to do.

25:34Then you adopt your parket files and then you're up then you're up and running. Um, also just wanted to show one of the cool things about Duck Lake is this is the this is a this is a working Spark connector in Python that is uh it's 30 lines of code, 34 lines of code, but most of that is sort of boiler

25:50boilerplate setting things up. Um, you know, so it's super super easy to do. And um if you just contrast that with how how how much code you'd need to build a working iceberg connector and have it be properly distributed uh I I guarantee it would be a lot a lot more than that. Um so just getting back to

26:09the you know the the sort of the design design points that we're looking at you know the small data small small compute duct DB rocks um if you if you increase the data size we have duck lake and we have hypertendency um if you increase the compute side we have rescaling and then um we have some for the the actual

26:29big data big compute we have giant instances uh and then ducklake which also can have external access.

26:36Thank you. [applause]

FAQS

What does Jordan Tigani mean by 'big data is dead'?

Jordan Tigani's thesis is not that large datasets don't exist, but that big compute, the need for distributed systems to process queries, is no longer relevant for 99% of workloads. Modern machines with hundreds of cores and terabytes of RAM can handle the vast majority of analytical workloads on a single node. The median database at Supabase, for example, is just 100 rows. Traditional distributed data warehouses were designed for the rare big-data-big-compute corner case, yet most users pay unnecessary latency and cost from that architectural overhead.

How does MotherDuck handle different data scale requirements?

MotherDuck addresses all four quadrants of data scale: for small data, small compute, DuckDB runs standard analytics at sub-second latency. For small data, big compute (like BI with many users), read scaling gives each user their own isolated DuckDB instance. For big data, small compute (like time series), DuckLake and hyper-tenancy handle large storage with targeted queries. For big data, big compute, MotherDuck offers instances up to 192 cores and 1.5 TB RAM, and DuckLake's open format allows Spark to process the same data externally.

Why are analytics AI agents well-suited for DuckDB's architecture?

Unlike text-to-SQL, which requires generating a perfect query in one shot, AI agents investigate data iteratively. They run multiple queries, pull in different data sources, and make decisions along the way. This maps naturally to MotherDuck's per-user tenancy model where each agent gets its own isolated DuckDB instance that can spin up in under 100 milliseconds. Agents can even clone and modify data independently without affecting other users or agents, then shut down when done.

What is DuckLake and why was it created as an Iceberg alternative?

DuckLake stores lakehouse metadata in a relational database instead of in files on S3 like Iceberg does. This gives it native transaction support, fast filtering and pushdowns, and much simpler setup: just two lines of SQL to create a DuckLake database. A working Spark connector for DuckLake is only about 34 lines of Python (mostly boilerplate), compared to the much more complex code required for an Iceberg connector. DuckLake was created by the founders of DuckDB and has been benchmarked at petabyte scale.

Related Videos

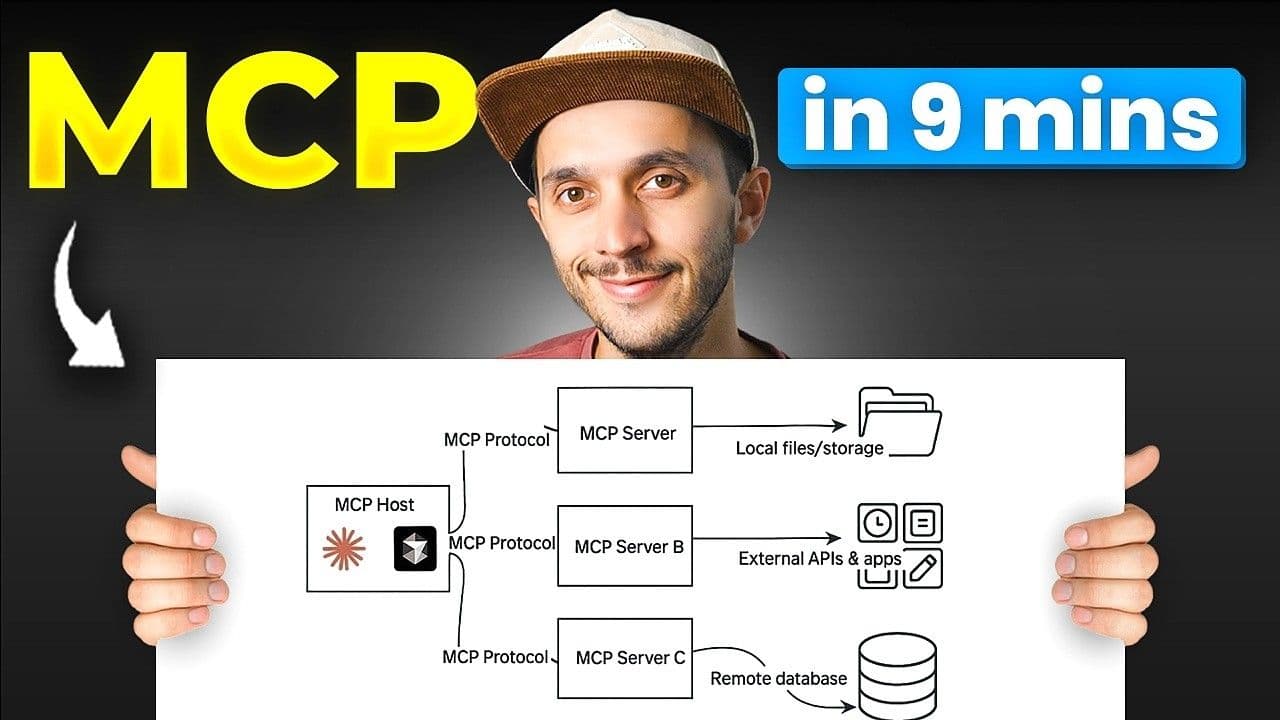

9:09

2026-02-13

MCP: Understand It, Set It Up, Use It

Learn what MCP (Model Context Protocol) is, how its three building blocks work, and how to set up remote and local MCP servers. Includes a real demo chaining MotherDuck and Notion MCP servers in a single prompt.

YouTube

MCP

AI, ML and LLMs

2026-01-27

Preparing Your Data Warehouse for AI: Let Your Agents Cook

Jacob and Jerel from MotherDuck showcase practical ways to optimize your data warehouse for AI-powered SQL generation. Through rigorous testing with the Bird benchmark, they demonstrate that text-to-SQL accuracy can jump from 30% to 74% by enriching your database with the right metadata.

AI, ML and LLMs

SQL

MotherDuck Features

Stream

Tutorial

0:09:18

2026-01-21

No More Writing SQL for Quick Analysis

Learn how to use the MotherDuck MCP server with Claude to analyze data using natural language—no SQL required. This text-to-SQL tutorial shows how AI data analysis works with the Model Context Protocol (MCP), letting you query databases, Parquet files on S3, and even public APIs just by asking questions in plain English.

YouTube

Tutorial

AI, ML and LLMs